Is ADHD a superpower? (part 3) - Traditional medicine and wisdom

Traditional perspectives on the treatment and meaning of "ADHD"

Part 1 here.

Part 2 here.

Traditional medicine

Doctors distinguish between “mainstream/modern/conventional” medicine and “alternative/complementary” medicine, which is an example of how modernity selects norms and then privileges systems that preserve them while accumulating wealth and centralising power in corporate offices and government bureaus. A better distinction might be made between complex or simple medicines. Traditional medicines are biochemically complex, which makes their effects on a biochemically complex system like a person impossible to understand from within a simple pharmacological model where “this molecule does this thing to this receptor”. This is a limitation, not of herbalism but of “the science” and of those institutions that prefer terms like “dopamine-reuptake” to “vata-reducing”.

This chauvinism also means that one of the major advantages of herbalism is overlooked and excluded, because while conventional medicines are usually single-molecule preparations, plants prescribed by herbalists are not – they often contain both compounds that produce the desired effects and also other compounds that protect the body from adverse effects. Any dopamine-boosting chemicals, including those in traditional medicines, will cause oxidative stress (as that is what increased dopamine does), and that will kill neurons and degenerate the brain. Unlike Ritalin, Adderall and the like, however, the herbal medicines listed below are also neuroprotective. Specifically, they contain antioxidants that prevent cell damage by free radicals.

While I don’t take pharmaceuticals, I do rev up my dopamine system, and my attention (far from being in deficit) gets so point-focused that I sacrifice sleep and forget basic self-care. As I enter my umpteenth late night in front of my computer, mainlining sci-hub and whiskey, I am pleased to reflect on how all of the medicines listed below reduce the damage done by increased dopamine – including that caused by the dopamine-hit chasing behaviours that people like me are prone to.

Ginkgo biloba

Gingko increases dopamine levels and is neuroprotective via various pathways, including as an antioxidant (helping against oxidative stress). It improves cognitive function and ADHD symptoms, but – in contrast to Ritalin – subjects also reported improved quality of life and mental health.

Gingko also has potent effects against anxiety, which is significant as, simply put, anxiety makes you stupid. Mildly anxiety-inducing images reduce scores in problem-solving tasks by half, and a person’s IQ drops by 13 points on average if measured when they are facing financial stress. My personal experience is that the negative sides of my cognition get much worse when I’m stressed out with application forms and calendars, and it can happen quite suddenly – I’ll be spinning 15 plates quite happily but if someone hands me a 16th I might drop them all and stop sleeping.

Rather than looking at this interaction, most of “the science” seems to be more concerned with measuring how the disorder of Generalised Anxiety overlaps with the disorder of ADHD, and medicating comorbidity more thoroughly. In any case, Gingko treats both at the same time. In fact, it was found to outperform suriclone and lorazepam in treating anxiety, and the effect was still increasing after four weeks while the effect of pharmaceuticals and the placebo had levelled out.

Frankincense

Frankincense is also neuroprotective, and works via ion channels to make dopamine receptors more responsive. I’ve discussed its psychopharmacology in a peer-reviewed article called Getting High with the Most High in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies and Drugs, the Israelites and the Emergence of Patriarchy on Lucid News.

Bacopa monnieri (Brahmi)

In Ayurveda, Bacopa monnieri is called Brahmi after Brahma, the creator of the universe, recalling its qualities of promoting creativity, calm and mental focus. It modulates dopamine, serotonin, GABA and acetylcholine, improving mood, memory and cognition. As well as making people cleverer (perhaps because they get less flustered when doing tests), this makes it useful in managing the more complicated aspects of (the cognitive style AKA) ADHD:

“Symptom scores for restlessness were reduced in 93% of children, whereas improvement in self-control was observed in 89% of the children. The attention-deficit symptoms were reduced in 85% of children.”

Given that Brahmi also treats hormonal imbalance, stress and anxiety, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, allergies, digestive issues and more, perhaps this brain tonic, rather than Ritalin, should be pushed onto schoolchildren. It certainly wouldn’t hurt – indeed, it is helpfully neuroprotective, containing antioxidants and mitigating Parkinson’s, meaning that you could take it along with Ritalin to reduce the damage.

Celastrus paniculatus (the Intellect Tree)

I recently met Acacea Lewis, a brilliant young autistic ethnobotanist who introduced me to another Ayurvedic medicine she prefers to Brahmi (traditionally the two are often combined). Celastrus, also called the Intellect Tree and Jyotishmati (meaning “lustrous”) is another dopamine booster with antidepressant action and neuroprotective effects against oxidative stress.

“These results suggest that C. Paniculatus might be useful in relieving anxiety, hyperactivity, reward-motivated behaviour and ameliorating the symptoms of ADHD by alternating neurotransmitter levels”

My dose is eight seeds whenever I remember to take it, and, subjectively speaking, I think it is wonderful. While it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of Celastrus and Bacopa (because I usually take whatever jar I come across first as I stumble around the chaos of my living arrangements), I’ve generally been both creative and calm despite recent stresses. The effect will, I believe, be more long-lasting and integrated than Ritalin, though it may be more subtle (as herbal medicines can be).

Mugwort and other artemisias

The artemisias are used in traditional medicine for conditions from whooping cough and IBS to burns and haemorrhage – as well as for anxiety and panic attacks. Like Diazepam, one path of action seems to be its effect on GABA receptors, though it outperforms Diazepam against anxiety. Like the other herbs listed above, it is neuroprotective and reduces oxidative stress.

In the lore of the Chumash Indian nation of California, parents stuff a handmade cloth star with Artemisia douglasiana and give it to a hyperactive child to play with to calm them down. Western medicine rarely employs scent, though it penetrates deeper into the brain than other senses and acts beneath the level of consciousness (which is why people have long spent huge sums on perfumes to make themselves seem sexier or more powerful). The olfactory centre is the ideal site of intervention to modify the behaviour of an overstimulated and anxious child: it is closely integrated with the amygdala which has a primary role in processing sensory input, modulating fear, anxiety and aggression, and making decisions.

As well as delivering the medicine steadily over an extended period, the star also requires that a parent invests time in their child to prepare the gift, perhaps gathering herbs and sewing the cloth together. This would set what NLP practitioners call “anchors” (and what doctors call “placebo”) in the mind that associates the scent and its effects with that act of love. Some of my earliest memories are of being told to sit still, in contrast to this wonderful intervention that integrates the fidgets of a hyperactive child into the remedy.

There seems to be more curative wisdom in this simple cultural practice than in the entire research department of Novartis.

When BBC runs headlines about “ADHD medicine shortage devastating families”, they are simply incorrect – there are plenty of medicines that have been shown to improve attention, including all of the above as well as Kanna, green oats, pine bark… There are hundreds of other traditional medicines which have not been tested yet. The problem isn’t the condition, nor the shortage; it’s a problem of definition, which is the problem with ADHD itself.

Conclusion

If Ritalin doesn’t help treat “ADHD”, what is it for?

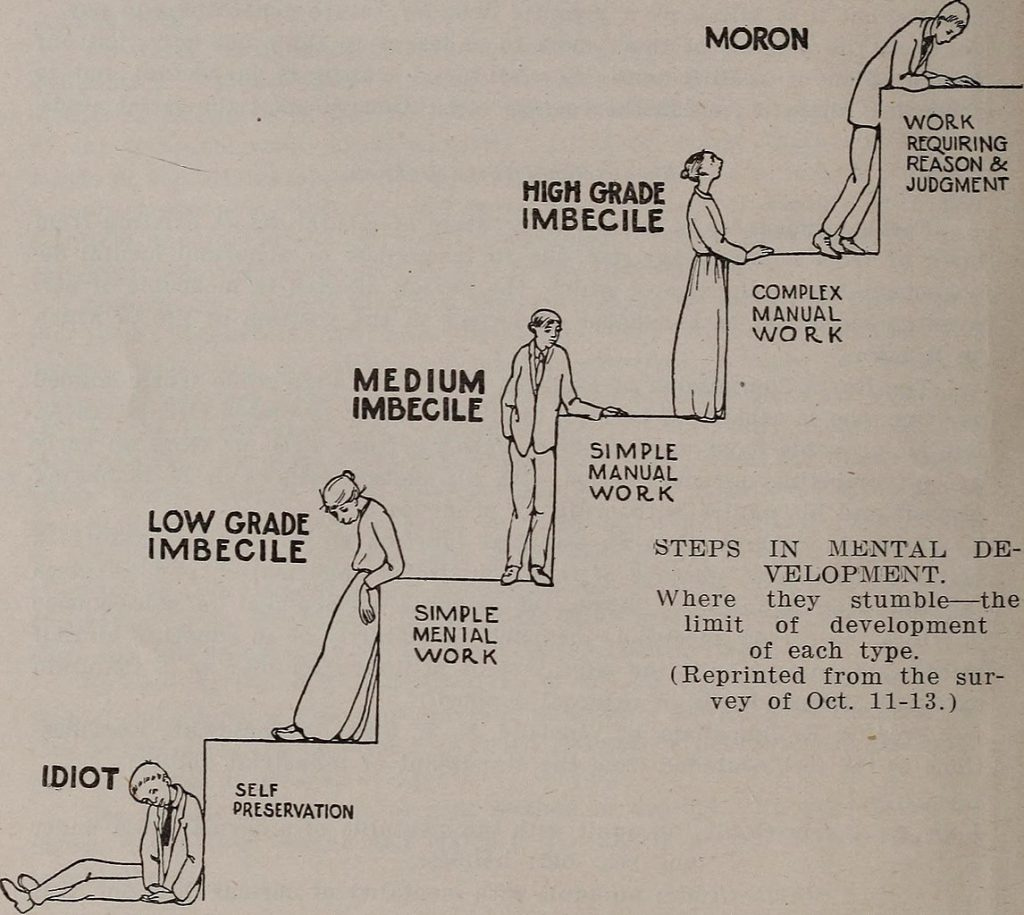

Foucault might have argued that my thinking is called a disorder, and medicated as such, for the same reason that escaping slaves were drapetomaniacs, women with high sex drives were nymphomaniacs and feeblemindedness was a burden on society – because it does not support the economic and cultural framework of a culture that mainly values people for their obedience and economic usefulness.

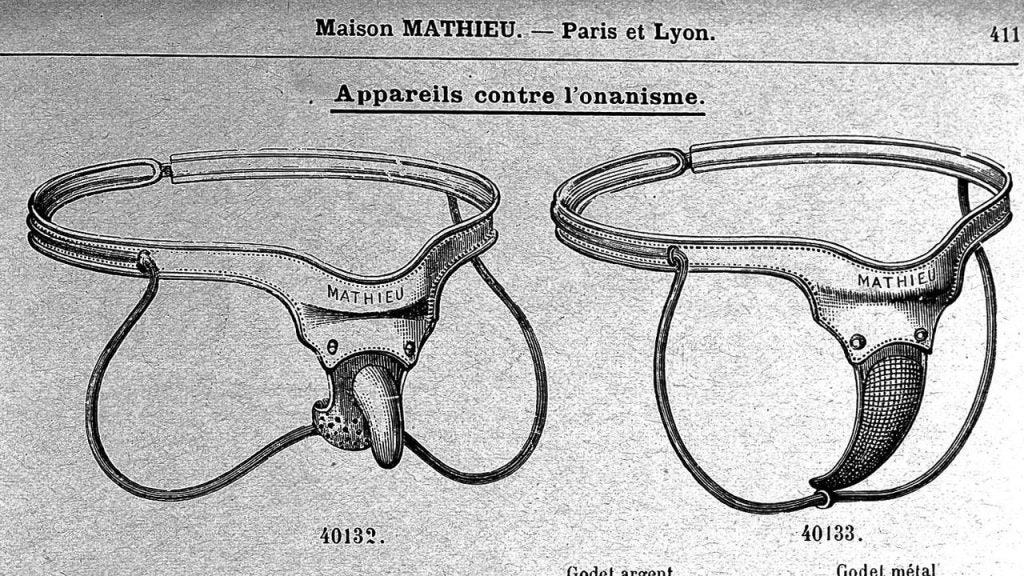

Parents managing their lusty daughters with chastity belts, slave owners slicing off toes, eugenicists seeking to preserve the fitness of their populations: these people were not monsters. They were products of a culture that was monstrous. Most people today agree that the most obvious excesses of the eugenics program were horrific, but a hundred years ago it was the most important scientific movement of the day, funded by such prestigious backers as the Rockefeller Foundation.

Some resisted the zeitgeist, including Dr Hans Asperger, one of the first to explore the upside of neurodiversity. He told a bunch of Nazis in Vienna seeking to exterminate his “little professors” just what they didn’t want to hear:

“not everything that steps out of line, and is thus abnormal, must necessarily be inferior”.

The sterilisation of inferior humans has fallen from favour, as have chastity belts and anti-erection devices, so we can rest assured for the time being that curbing uncivilised tendencies with mechanical interventions to the genitals is out of fashion. Today we curb uncivilised tendencies with pharmacological interventions to the brain, and once again the Rockefeller Foundation is funding “the science”. We do this to our children out of a genuine sense of love and affection, and we do it to ourselves. With campaigns like #ADHDAwareness bleeding from the wound that identity politics has inflicted on our psyches, the neurodivergent themselves are vocally demanding that they be recognised as legitimately deficient.

In nature, diversity announces the health of an ecosystem. I believe that in human nature neurodiversity is a blessing. As Asperger put it:

“It seems that for success in science and art, a dash of autism is essential … the necessary ingredient may be an ability to turn away from the everyday world, from the simply practical, an ability to rethink a subject with originality so as to create in new untrodden ways.”

We’re annoying, to be sure, especially to people who are set in their ways. But from the perspective of a weirdo on the fringes, we’re not half as annoying as nautists. Sometimes neurotypical cognition looks like a baby trying to learn how to use a spoon, self-obsessed and oblivious. And the mess you make of things!

Temperance

A virtue of great interest to metallurgists of the Middle Ages was temperance, and the idea persists today in the idea of “keeping your temper”. In medieval hermetic philosophy, swords represent the mind and the faculty of language, and the training of the mind is likened to the hardening and tempering of a blade. A bladesmith subjects the metal to cycles of extremes, heating it until it glows red and cooling it by quenching it in water or oil. This conditions the sword and makes it hard enough to hold a sharpened edge. The work is complete when a strike to the sword makes it sing.

The sound resonates because the atoms of the metal have been brought into an orderly lattice that transmits a wave along its length and into the air. This lattice also gives the blade its hardness so it can hold its edge, as any forces it is subjected to are distributed evenly throughout the metal. The final quenching leaves it so hard as to be brittle, so the last process before sharpening is to temper it by heating it evenly in the forge, sacrificing a little hardness for more flexibility. With the correct combination of hardness and softness, a blade well wielded can slice through armour. Its edge cuts and its point penetrates, but it is flexible enough to sing rather than break when it parries an attack – which is a good way for our minds to be.

Since humans developed thumbs that can oppose our fingers and egos that can oppose our natural urges, part of the task of life is to bring our intelligence and creativity into the world harmoniously – to sing our own song in the chorus of the whole. For uncountable generations, adolescence has been a time to experience and confront extremes, and traditional societies invariably supported their passage into adulthood with initiation rituals that subjected the child to extremes. Teenagers are driven to test the limits of our worlds, and the feistier ones can be extremely testing. It’s a testing time for young people and their parents alike, but that’s the deal with parenthood. In my mind, at least, education is what the etymology suggests: e (out) + ducare (to lead). It is about leading something out and assisting with the challenges that entails, not keeping it in.

Keeping it in may be appropriate for a time, but not for a long time. Since ADHD was invented and Ritalin found a market, increasing numbers of people have gone through significant chunks of their adolescence with their neurotransmitters being managed from the outside with pharmaceuticals. They are protected from extremes, denied the opportunity to learn how to harness their powers and kept in an infantile state. But unless they are going to medicate all the way to the Pearly Gates, at some point they will have to rise to the challenge.

The more that can is kicked down the road, the worse it gets because habits of the mind and pathways in the brain become much harder to modify in adulthood. The world becomes less forgiving as you grow older too. A 12-year-old can get into fights with their peers without causing too much damage as their muscles aren’t fully developed; an 18-year-old picking fights is a different matter. Minors have less of a career to derail, fewer serious relationships to trash, no car to drive distractedly… And people – including the police and the justice system – treat youngsters more leniently. An unregulated 15-year-old is annoying. An unregulated 23-year-old is a menace to society and will be punished as such.

Coming back to balance

When people say “I have ADHD so I have a unique viewpoint”, it sounds better than “I have ADHD so I can’t concentrate”, but it is also insulting to nautists (who are, after all, quite a diverse bunch). What a psychiatrist says – what they are financially rewarded to say – need have no bearing at all on how you present yourself, and any feel-good happy zebra factor is bound to be stained by the downsides of the diagnosis. ADHD isn’t a superpower. It’s just a diagnostic category. If you also have a superpower then lucky you. And also poor you! Every comic fan knows that superpowers come with downsides and that superheroes are tested as much by the world as by supervillains.

Leaving aside larger questions and polemics: while Ritalin boosts dopamine, it also brings problems that are not found with other dopamine-boosting practices such as hypnosis, cold plunges, exercise, breath work, herbal interventions, love, sex, crazy dancing and much more. Such practices go beyond managing symptoms to developing the powers that emerge when we come to terms with ourselves and allow our unique natures to flourish.

Coming off of meds is a serious step, as anyone who has dealt with addiction knows. In the case of ADHD, it is as if the bike is liberated from its stabilisers. Suddenly we’re cycling in traffic and wanting to pull a wheelie, but a sense of balance takes time to become established. When people decide to start cycling their brains properly again, they need to develop new habits that do what Ritalin does but better. I wouldn’t recommend anyone even begin coming off medication without having established a daily practice of guided breathwork for at least two weeks first, and then keeping it up daily for at least another six weeks. A therapist or hypnotherapist could be a great help, so could a stack of herbal supplements and a support group or neurodivergent mentor.

Part of the work is developing self-love, and – without going too deeply into the changes in culture over the last fifty years – many of us have grown up without good models of care from our primary caregivers. This affects both nautists and the Asper(ger)ational, but differently. Growing up weird is especially tough when your parents don’t have the resources or framework to help you deal with it.

To begin with, if you believe you are managing a pathology rather than nurturing your genius, you haven’t embraced your own cognitive style yet. Self-love begins with self-acceptance, and that may require rejecting the labels, projections and expectations put upon you – including those from other people who want you in their deficient and disorderly spectrum, sharing their hashtags. Of course, I have traits in common with other people with an ADHD diagnosis, and some of my closest friends are functionally catastrophic individuals who live in chaos. But I share far more traits with Donald Trump, Bruce Lee and Audrey Hepburn (number of eyes, kidneys and fingers, for example). It is our differences, not our similarities, that define us and make us unique and interesting, and if there is any hope for us at all it is in the integration of diversity rather than the fragmentation of humanity. So come round, let’s have a party, you can help me organise a cupboard and I’ll have a rant about the Oxford comma – we need each other. Besides, I don’t want to be defined alongside people with a mental disorder and an acronym, and I’d rather not be set apart from the rest of humanity any more than I already am.

Maybe there’s no collective noun because we aren’t much of a collective?

Psychiatric drugs keep us from the extremes, they keep us from sharpening and tempering our own unique minds until they sing; ultimately, I believe, they keep us from reaching our full potential. Of course, many people who use Ritalin are still creative, but how much more creative might they be if their innate powers were unleashed rather than tethered? Perhaps, scaling out to view history and humanity as a whole, the real tragedy is that these interventions keep from the world the solutions we desperately need to rise to the challenges that we face in the 21st century – the kind of solutions that come from violently creative people thinking outside of the box.

Coda (to a coder). I did eventually get hold of an earlier version of this piece that wasn’t erased, as a tech genius who had edited it raided his cache for me. I’d say he’s been on the Spectrum since he was born, but he’d upgraded to an Amstrad PC1512 by 1986 and today he is programming AI Large Language Models. Thanks John!

For more on how “The Science” manages our perceptions of reality in a manner most unscientific, check out my book Science Revealed. For a deeper dive into neurodivergence, opposable thumbs and the revolutionary potential of thinking differently, have a look at Neuro-Apocalypse. And if you think hypnosis can help, try the free taster sessions at pattern-interrupt.co.uk.